Economics 101

Economics Cannot Exist Without Ecology: We Need Ecological Economics For All

“The economy is a wholly owned subsidiary of the environment, not the reverse.”

Important note about the information you are about to access: We are constantly developing this innovating and evolving open-access virtual textbook on real economics because we believe that this information is essential to understand why and how we might transform our fossil fueled socio-economic systems to achieve wellbeing within planetary boundaries for all. We aim to overcome barriers to information sharing in academia and publishing by making this information readily available and accessible to diverse audiences interested in rethinking economics to confront our most pressing and intertwined social and ecological crises. We hope that the information below helps you get a better idea of what is supposed to be role of the economy in our daily lives. If you have content contributions you would like to see on this site send us your open access and referenced material at the bottom of the page.

1. An Innovative & Evolving Open Access Virtual Textbook for All!

2. Why should you care about the story that Ecological Economics For All has to tell?

We all care about our wellbeing and that of those who we love. Our wellbeing ultimately depends on a healthy and thriving environment and society. Therefore, we should want to secure our livelihoods and that of future generations by living in a world where we can ensure that our needs are sufficiently met by ecological economic systems that are sustainable, just, efficient and resilient in the short- and long-term.

To fully appreciate this new economic story, we have to understand 3 basic principles:

(1) Economics cannot exists without ecology, and, thus, economies cannot grow indefinitely on a finite planet;

(2) The economy exists to serve people and planet and not the other way around, i.e. not in service of GDP growth for the sake of growth; and

(3) Society has to be understood as being a part of the ecology of the Earth to develop ecological economic systems that can achieve a mutually enhancing relationship with the rest of nature.

Our philosophy is that anyone who cares about nature, justice and time can be an ecological economist because human beings need to live in harmony with all 3 of those components to thrive on our finite planet. The information below should serve as a guide to understand how the economy works within its social and biophysical foundations so that we can envision post-growth well-being futures for humans and the rest of nature.

The following information and its organization is largely inspired by Røpke (2020) who suggests teaching how real, coevolving, dynamic, and far from equilibrium economies work starting with the study of the biophysical and social foundations in which they are embedded. Issues of efficiency and critiques of mainstream economics are covered after those biophysical and social foundations are established to understand why and how the economic systems of today could be transformed to a post-growth paradigm to achieve wellbeing for all within planetary boundaries.

3. Theory and Principles For a Just Sustainability Transition to a Right-Sized Economy

“A sustainable society is one that can persist over generations, one that is far-seeing enough, flexible enough, and wise enough not to undermine either its physical or its social systems of support.” - Donella Meadows et al., 1992. Beyond Limits

4. What is Ecological Economics?

Ecology and economics share the same Greek root, eco or oikos, meaning “household”. Ecology means the study of the house, while economics means the management of the house. Ecological economics takes the house to studying and managing humans impacts on the world through an integrated and systems thinking approach to foster genuine wellbeing for people and the rest of nature by taking full advantage of our accumulated knowledge and understating of both the natural and the social realities of our planetary system.

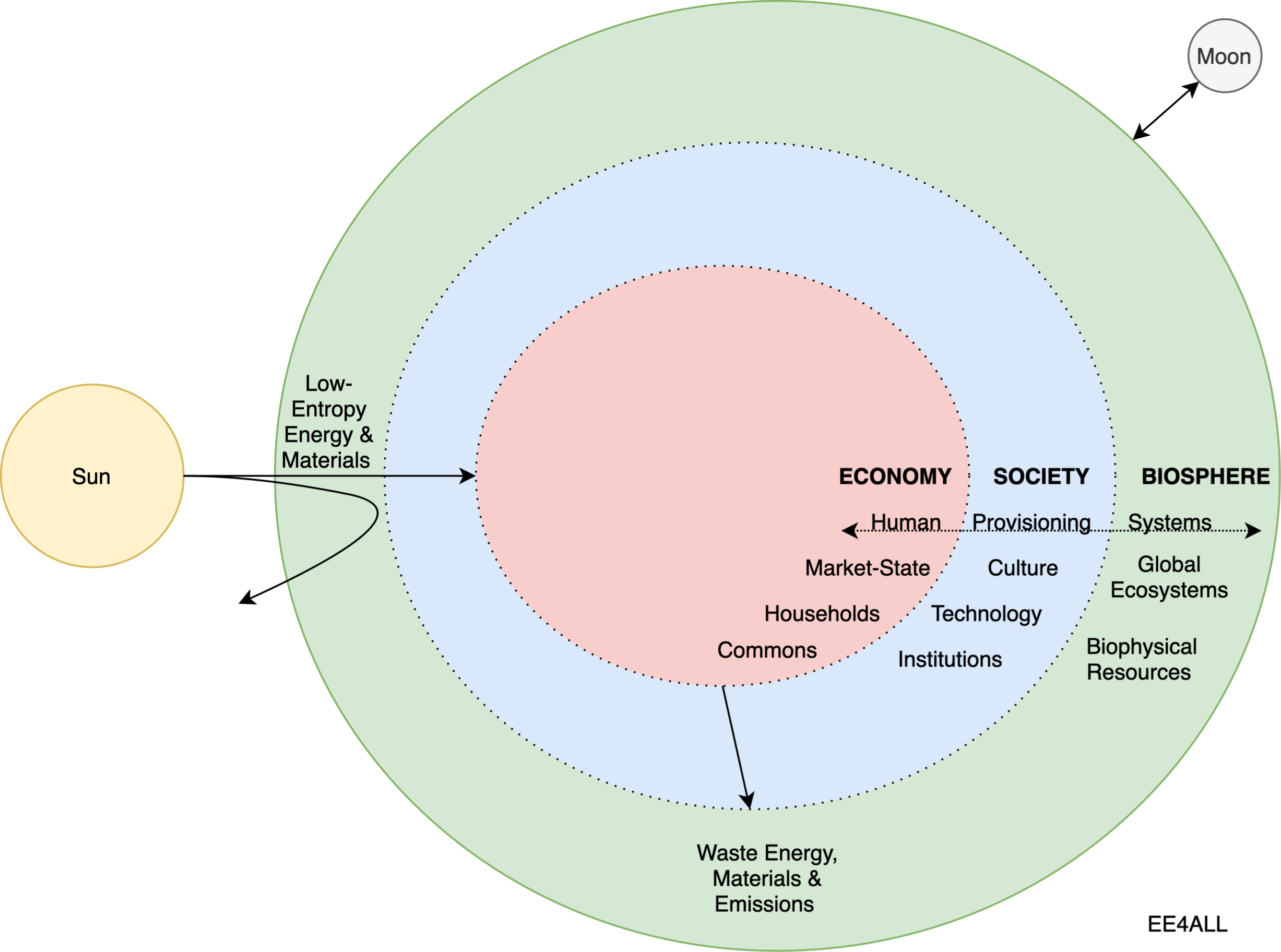

Ecological Economics implicitly (and at times explicitly) adopts Polanyi’s substantive definition of economics as how humans interact with society and nature to provide for their material needs. In a nutshell, Ecological Economics acknowledges that the economy is embedded in society which in turn is embedded within the biosphere of the Earth (See the simple planetary ecological economic model below). All economic production requires low-entropy (available) energy and raw materials, which the economic process converts into goods and services that contribute to human well-being, but ultimately break down, fall apart and return to our ecosystems as waste. It is possible to recycle some material flows, but not energy. Our finite planet provides finite stocks of raw materials and energy, the latter primarily in the form of fossil fuels. In sum, Ecological Economics studies how the economy can serve humans to improve their quality of life, while maintaining a healthy and thriving ecological foundation on which humans and the rest of nature depend on to exist.

The Economy is Embedded in Society

Humans are arguably the most social species to ever evolve. A single human is no more capable of surviving independent of human society and collectively generated knowledge than an individual human cell independent of a human body. In the modern world, simply feeding ourselves requires immense knowledge not only of agronomy, but also of all the other knowledge required to manufacture and fuel the innumerable tools we use to produce, harvest, transport, store and cook food. No single human brain can possibly contain all that knowledge. Rather, human culture, which includes knowledge as well as the rules, norms, and institutions that enable us to cooperate, is cumulative and collective, created by billions of people over thousands of years. All economic activity requires social interaction.

This figure shows a simple planetary ecological economic model where the economy is embedded in society and the economy and society are embedded in the biosphere. Beyond this embeddedness, however, human interconnectedness with the biosphere can be better understood as a cross-cutting relationship among the economy, society and the biosphere connecting the market-state (there is no market without the state), households, commons, human culture, technology and institutions, with the global ecosystems and the biophysical resources that underlie all human provisioning systems.

Ultimately, most of the energy that is available on Earth comes from the sun, which strikes the earth at a fixed rate over time. The Earth absorbs 70% of the solar radiation and reflects ~30% back into space. Fossil fuels are solar energy stored from millions of years ago and remain our main source of energy today. The moon’s gravitational pull generates the tidal energy of the oceans, influences the length of day, helps to maintain stable seasons, and it may even influence the movement of tectonic plates. The biosphere provides us with low-entropy (available energy to do work) energy and material inputs that humans transform in their economic processes into wellbeing. The waste energy, materials and emissions from economic processes end up in the biosphere. Source: Ecological Economics For All

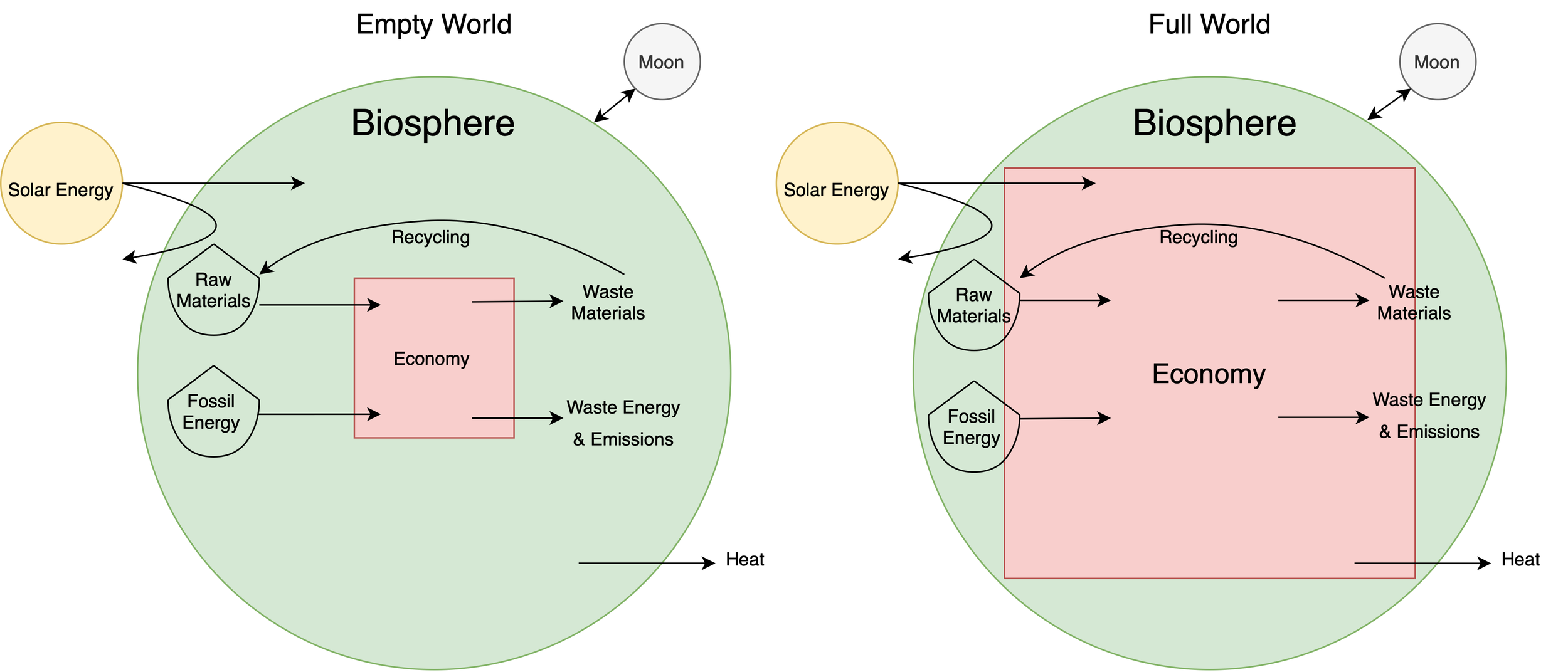

Humanity has Shifted From an Empty World to a Full World

Today, the story and vision of Ecological Economics is more important than ever because humanity has shifted from an empty world with a small human population and low levels of per capita consumption, to a full world in which 8 billion humans and their livestock account for 96% of mammalian biomass and the average human consumes as many calories as would a 30 ton gorilla. In an empty world, human populations and consumption levels of energy and materials were too small to have significant impacts on vital ecosystem functions. In today’s full world, the goal of economic growth leads to massive transfers of wealth to the few at the top, while it undermines the wellbeing of society and the rest of nature. Thus, economic growth becomes what Herman Daly termed “uneconomic growth” or growth where the social and environmental costs outweigh the benefits of more fossil fueled economic production. Today's globalized economic system unequally distributes resources to the high income populations within and between countries leaving the most in need behind, while the accompanied impacts on resource depletion, natural cycles, biodiversity loss have planetary and social consequences such as inequality, hunger, climate change, the Covid-19 pandemic, etc. Ultimately, the economy of a full world threatens to irreversibly cross planetary boundaries and harm the long-term wellbeing of all. This predicament requires a sustainability transition to a right-sized and post-growth economy informed by ecological economics and other heterodox schools of economics.

This figure shows what Herman Daly characterized as “the shift from the empty world to a full world” that has occurred in population growth, economic growth, and energy and material resources consumption since the Great Acceleration that began in the 1950s. It is important to point out that the shift to a full world began with the agricultural revolution 10,000 years ago which gave way to the “economic superoganism” that has culminated with today’s global capitalism and the separation of humans from the rest of nature. The impact of the global economy has increased to unprecedented levels, with the climate crisis and inequality as prime examples of why we need a sustainability transformation to a right-sized economy that fosters a mutually enhancing relationship between humans and the rest of nature. Source: Ecological Economics For All

5. A New Economic Story Requires Transcending Disciplinary Boundaries

Ecological Economics is an interdisciplinary (synthesizes and links disciplines) and transdisciplinary (transcends disciplinary boundaries) field that as Costanza et al. put it in 1991 is dedicated to the science and management of sustainability. Ecological Economics not only bridges across ecology and economics, and other social sciences (e.g., history, sociology, anthropology, psychology, archeology), natural sciences (e.g., physics, biology, chemistry, geology, environmental science), and humanities (ethics, philosophy, history), but it also includes other heterodox economic theories (e.g. political, post-Keynesian, feminist, institutionalist, evolutionary), and non-academic experiences and expertise in its new economic story to address complex and intertwined environmental, social, and economic sustainability problems. By transcending disciplinary boundaries Ecological Economics is able to inform a post-growth paradigm shift vision that works for people and planet.

A Socially and Ecologically Grounded Post-Growth Paradigm Shift Vision For Economics

Ecological Economics was created to foster a socially and ecologically grounded post-growth paradigm (i.e. model/thought pattern) shift in economic thinking. This paradigm shift is based on the reality that socio-economic systems are embedded in the biophysical world of energy and matter, and these systems must ensure wellbeing without destroying the biosphere. It calls for abandoning unsustainable, unjust, and inefficiency economic processes and resource consumption patterns adopted since the 1950s during the Great Acceleration and enabled by abundant and cheap fossil fuels and the financial institutions that govern the supply of money.

The historical roots of Ecological Economics’ paradigm shift vision can be traced back to how ecology and economics share the same Greek root, eco or oikos, meaning “household”. Ecology means the study of the house, while economics means the management of the house. Ecological Economics takes the house to studying and managing humans impacts on the world in an integrated and systems thinking way to foster genuine wellbeing by taking full advantage of our accumulated knowledge and understating of both the natural and the social parts of our planetary system.

Click on the link below for a more detailed historical recount of the roots of Ecological Economics, and to learn about how early economic schools of thought had a biophysical and political basis:

History of Ecological Economics

The Economy and Society are Embedded in the Biosphere:

6. The Biophysical Foundation of Socio-Economic Systems

"Anyone who believes in indefinite growth on anything physical, or a physically finite planet, is either a madman or an economist” - Kenneth Boulding (1973) while providing evidence to the US Congress in the wake of the Limits to growth report by the Club of Rome.

The economy and society are embedded in the biological and physical (biophysical) world of energy and matter. Energy, defined as the ability to do work, is an essential input to transform matter in economic processes that provide society with material well-being. In 1989, Ecological Economics was founded by ecologists and economists who realized that all ecological and economic processes shared a biophysical foundation involving low-entropy matter-energy, well functioning ecosystems, and natural sinks, from the production of economic goods and services to the dissipation of the high entropy waste that such economic processes inevitably generate (see biophysical model of the economy below).

The biophysical foundation of economies is anchored in the laws of thermodynamics. The first law of thermodynamics (the law of conservation of energy) states that the total quantity of energy is conserved, while the second law of thermodynamics (the entropy law) states that the total quality of energy is not conserved. This can help us to understand that we can’t make something from nothing and you can’t do work without energy that degrades with use into high-entropy unavailable energy. We have raw materials provided by our planet, which alternatively serve as the building blocks of global ecosystems that we need to survive. This implies that there are significant planetary limits to economic growth that need to be considered to avoid undermining our environment, and , thus, prevent ushering in the collapse of civilization.

As of 2020, 85% of the energy we use in our economy is fossil fuels. When we burn them, we create pollution and accelerate climate change which harms both humans and the rest of nature. For example, the U.S. economy has increased in size at least 20 fold in the past 100 years, causing enormous harm to ecosystems. In the past 4 decades, most of the gains have gone to the rich, who need it least. When they take more from our finite planet, it leaves less for present and future generations, and we all pay the costs. This is unsustainable, unjust and inefficient.

The biophysical model of the economy shows the different stages that allow for the economic process to take place, starting with the natural energies, raw materials and their exploitation to the processing, manufacturing and final consumption. Every stage from exploitation to consumption requires energy transformations, technology, labor and capital to achieve final demand. Energy and raw materials flow to the economic stages, ultimately, heat released to the environment are depicted in yellow, material flows in blue; natural processes in the left most two sections and economic processes to the right. For example, the model shows fossil energy and raw materials at the exploitation stage flowing to a refinery in the center of the processing stage and the natural gas plant under it, which mediate the energy and material flows necessary for further exploitation, manufacturing and consumption. This model, as opposed to the biophysically incorrect “firms and households” model normally given in economic textbooks, emphasizes the mostly one way flow of economic systems from nature to wastes. Source: Melgar and Hall (2020).

A Sustainable, Just & Efficient Energy Transition

A just energy transition is an essential pillar of a sustainability transition to a right-sized economy. This is why understanding the biophysical and social foundations of economies is going to be essential for an energy transition to be sustainable, just, and efficient. Many countries are embarking on an energy transition to low-carbon energy resources to address long-term issues of cheap fossil fuel depletion, climate change impacts, and inflationary pressures that will arise from the fact that virtually all economic activity today is dependent on an inflow of cheap fossil energy. However, an energy transition of this magnitude requires an understanding of the social implications of the biophysical and financial investment requirements needed to achieve it, while staying within the global carbon budget to avoid the 2 degrees Celsius temperature increase that the IPCC has warned about.

The system dynamic En-ROADS interactive energy-economy model is a great hands on source to learn about systems thinking and to think critically about the biophysical foundation of the economy and its societal implications for climate change as well as the different leverage points that might help us achieve a sustainable and just energy transition.

EE Concepts for an Energy Transition

The following are biophysical and ecological economic concepts framed within the 3 Ecological Economics goals of sustainable scale, just distribution and efficient allocation (more details on these goals below) that build on each other (we need to understand what is sustainable scale of energy systems to inform what could be the just distribution that can enable us to achieve efficient allocation of energy for wellbeing) to help us think logically, critically, and systematically about energy transitions to ensure that they are sustainable and equitable in the long-term (based on Melgar and Burke, 2021).

Concepts that inform the sustainable scale of energy systems:

The two pillars for understanding energy and what we can do with it are the quantity of exergy (available energy to do useful work) or anergy (unavailable energy to do useful work aka high entropy heat), and the quality of energy as determined by the difficulty in obtaining energy, energy density, and physical and social difficulties of access. The difference in quantity and quality means that not all energy can enable us to do the same work, which has deep consequences for the useful work that we can do with either renewable and non-renewable energy sources.

Another concept is energy sufficiency which informs how wellbeing can be achieved by meeting peoples basic needs for energy services equitably and within planetary boundaries. Energy sufficiency proposes a maximum level of energy consumption that is ecologically sustainable combined with distributional justice to ensure everyone has fair access to energy to meet their needs for wellbeing.

Concepts that inform the just distribution of energy systems:

In this goal, the biophysical needs and limits of obtaining an energy surplus are measured as net energy or energy return on investment (EROI or EROEI), which helps to clarify the trade-offs among different sources of energy. The EROI needs to provide a positive ratio of energy returned to society from the energy invested to have enough energy surplus for reinvestment in obtaining more energy without compromising society’s ability to meet its basic needs.

The social needs and limits for this goal are influenced by the rebound effect or Jevons paradox, which states that increasing improvements in energy efficiency often lead to higher demand for energy in new technologies, reducing and potentially cancelling out efficiency improvements.

Concepts that inform the efficient allocation of energy systems:

The efficient allocation of resources is where neoclassical economics and policies thereof place most of their focus. However, from an Ecological Economics perspective, one cannot allocate energy resources efficiently without first establishing what is the sustainable scale and just distribution for a given population.

Therefore, the biophysical needs and limits of this goal relate to the energy quality and transformability enabled by energy quantity and surplus from a sustainable scale and just distribution, respectively.

The social needs and limits under this pillar concern the energy footprint that, if too large, can cancel out energy efficiency improvements (if we can even achieve them).

This goal also requires pertinent decision-making to enable financing and purchasing power of people who are left out of the access to energy and technologies, and information and resource sharing to increase the adoption of low-carbon technologies and improve their EROI.

This figure shows the energy concepts within the 3 goals of ecological economics. Source: Ecological Economics For All

From Ecological Economics to Doughnut Economics:

Thriving Within the Limits of Planetary Boundaries

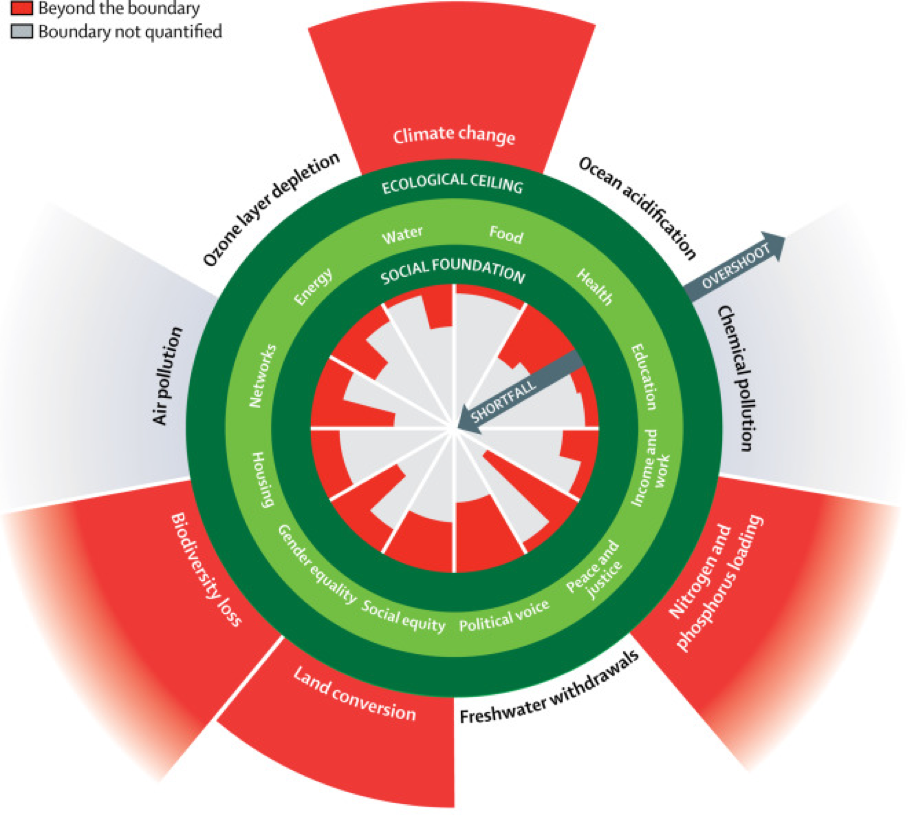

We recognize that energy and materials are the means to achieve our ends; the goods and services that they enable for our well-being. Ecological Economics provides a path for a prosperous life within planetary boundaries in which polices and decision making are based on protecting the biophysical foundation, while ensuring that we can provide society with the necessary requirements for a good life under a regenerative and distributive economy. Kate Raworth built on ecological economics to derive her “doughnut” economic model, which is an excellent representation of this path because it provides explicit social goals that must be met within planetary boundaries. The figure below shows the green doughnut of the safe and just space that humanity must stay in between the “ecological ceiling” and the “social foundation” including 12 social needs: energy, water, food, health, education, income and work, peace and justice, political voice, social equity, gender equality, housing, and networks. The shortfall in social needs must be overcome by staying within the ecological ceiling to avoid an overshoot of our planetary boundaries. However, as the figure shows, we have already crossed the climate change, biodiversity loss, land conversion and nitrogen and phosphorus loading planetary boundaries, which makes the vision of EE for a sustainability transition more necessary than ever. Learn more about a good life within planetary boundaries and your country’s trends.

Source: Kate Raworth and Christian Guthier/The Lancet Planetary Health

The Social Foundation of Economies: The Need for a Cultural Transformation

The economy must be subservient to society and not the other way around. Economies are supposed to exist to enable society to allocate, as sustainable and fairly as possible, the biophysical requirements for wellbeing. However, the obsession with economic growth that fossil fuels have facilitated since the 1950s has led to economic systems that are increasingly undermining the quality of life of humans and the rest of nature as represented scientifically by the planetary boundaries and the doughnut of the safe and just space above. This calls for a cultural transformation away from unsustainable economic systems and consumption patterns that is based on cooperation, respecting our planetary boundaries, and promoting sustainable and fair allocation of resources within countries and between the global north and south. The field of Ecological Economics has been thinking critically and systematically to develop social-ecological theories and principles to understand the biophysical and social realities needed to make economies sustainable. Now, more than ever, we need everyone with an open mind to understand how we can all make a real sustainability transformation a reality by making use of this accumulated knowledge.

6. Theoretical Foundations of Ecological Economics for A Sustainability Transition

The 3 Goals of Ecological Economics for

a Sustainability Transition to a Right-Sized Economy

The main 3 goals at the foundation of EE include understanding how a sustainable scale, just distribution, and efficient allocation of resources can be achieved in a way that promotes a prosperous way to a sustainability transition within planetary boundaries. The premise behind these 3 goals is that we cannot address our sustainability problems without an understanding of what is the economic scale of energy and materials consumption that our localities, regions, countries, and planet can sustain in the long-term. A sustainable scale informs how society can justly distribute natural resources to ameliorate inequities within countries and between the global north and south, while keeping in mind future human generations and the rest of nature. Finally, after knowing what is the sustainable scale and just distribution we can efficiently allocate resources in a way that avoids further crossing our planetary boundaries (the figure below uses energy and materials to understand how we can think about the 3 pillars of EE). Failure to achieve sustainable scale and just distribution lead to uneconomic growth, in which the ecological and social costs of additional economic growth come to exceed the economic benefits, leaving society worse off than it was before.

The pillars of ecological economics can serve as the foundation to understand the biophysical and social needs and limits to achieve more sustainable outcomes in generation of material well-being for society. First, we need to understand what is the sustainable scale to inform the just distribution necessary to efficiently allocate energy resources. Source: Ecological Economics For All

What is the sustainable scale for the economy?

Conventional economics is often defined in Econ 101 textbooks as the study of the efficient allocation of scarce resources among people with unlimited wants, where efficiency boils down to the maximization of monetary value. However, in Ecological Economics we understand that our economy is sustained by the ecological functions of our finite planet. It therefore prioritizes the goal of institutions to promote a desirable sustainable scale to achieve wellbeing within planetary boundaries: how much of nature’s finite resources can be transformed into economic production, and how much must be conserved to generate life sustaining ecosystem functions for all species?

For a society’s economy to be biophysically sustainable it needs to meet at least three conditions in its energy and material throughput (inputs/outputs) as per Herman Daly: (1) Its rates of use of renewable resources do not exceed their rates of regeneration; (2) Its rates of use of nonrenewable resources do not exceed the rate at which sustainable renewable substitutes are developed; and (3) Its rates of pollution emissions do not exceed the assimilative capacity of the environment. The sustainable scale for an economy can be further informed by:

Biophysical Economics and Ecological Macroeconomics

Circular Flow Model & Growth Theory, Limits to Growth, and Planetary Boundaries

Fossil Fuels and Other Abiotic Resources

Ecosystems and Other Biotic Resources

Social Metabolism

Agroecology and EE

Sufficiency

How we can achieve the just distribution of natural resources for present and future generations?

After having an idea of what a sustainable scale for an economy can be, we can know what resources we have to distribute justly among the population without undermining the rest of nature. Thus, a second goal for Ecological Economics is the just distribution of our shared inheritance from nature, within and between generations, between the global north and global south, as well as the just distribution of wealth produced collectively by society as a whole.

Intergenerational Distribution

Ecological Governance and the Commons

Just Distribution of Essential Resources

How we can promote the efficient allocation of natural resources to reduce waste, inequality, depletion, and the deterioration of our planet?

It is not until we understand what is a desirable scale and consider how to justly distribute our limited resources sustainably and equitably that we can efficiently allocate resources. Therefore, a third goal for Ecological Economics is efficiency: given finite resources, how can we attain sufficient well-being for all at a minimum ecological cost?

Money and its Role in Sustainability

The Market and its Failures

Globalization and International Trade

If you enjoyed this open access virtual textbook please consider donating or recommending donors to continue our much needed work to ecologize economic thinking!

Submit Content

Would you like to read more about ecological economics? These are some of the key publication on which the information above is based on.

Daly, H.E. and Farley, J., 2011. Ecological economics: principles and applications. Island press.

Faber, M., 2008. How to be an ecological economist. Ecological Economics, 66(1), pp.1-7.

Røpke, I., 2020. Econ 101—In need of a sustainability transition. Ecological Economics, 169, p.106515. http://www.ecomacundervisning.dk/?lang=en